Casey Mulligan Swings and Misses

October 28, 2009

University of Chicago economist Casey Mulligan has a post today at the New York Times Economix blog where he seems to argue that the current push for statutory paid sick days in the United States is ignoring the role of economic incentives. According to Mulligan, workers in countries with generous paid sick day policies stay home because of "incentives, and not the flu".

I don't think Mulligan has been following the U.S. debate on paid sick days very closely. The U.S. debate is very serious about incentives. The current system --which does not require employers to provide paid sick days and leaves upwards of 50 million workers without paid sick days-- gives strong incentives to workers to go to work sick, lowering productivity and potentially spreading illness.

Of course, offering paid sick days also gives workers incentives to take time off when they are not sick. But, there is nothing in Mulligan's post that says where we should set the optimal level. He doesn't even make a case that the most generous systems in Europe are too generous, just that they lead to more sickness absences in some cases. For all we know, after we factor in the cost of contagious diseases, the most generous European systems might still be too stingy.

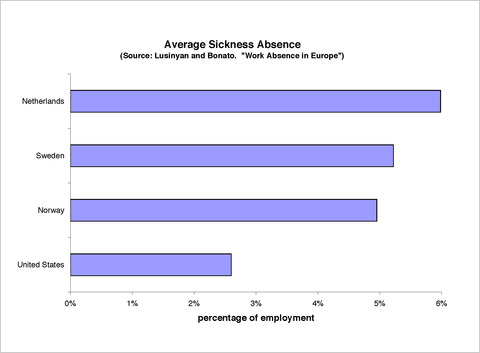

To make his point about the effect of incentives, Mulligan features the following graph from a recent IMF paper:

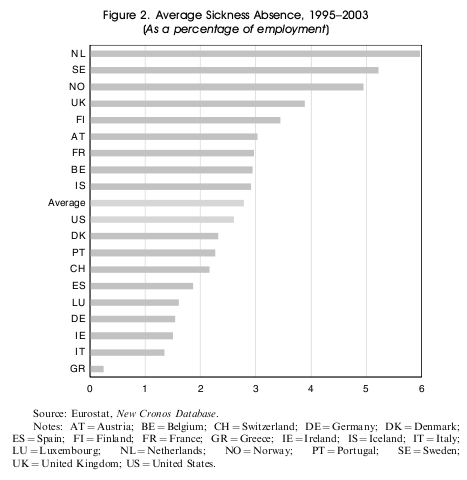

Mulligan, however, has made very selective use of the original IMF graph:

In the original, Denmark, Germany, and seven other countries with more generous statutory paid sick days policies all have lower sickness absence rates than the United States. A really interesting question is: how is it that these countries are able to provide both guaranteed paid sick days and lower sickness absence rates? (And why didn't Mulligan include these countries in his graph?)

UPDATE 11/10/09: Salon's Andrew Leonard ("How The World Works") wrote a nice piece linking to this post. So did Nick Baumann at Mother Jones. Casey Mulligan responds to the concerns raised here on his University of Chicago blog, but makes no mention of any of these issues at the New York Times' Economix blog, where his original post appeared.